A Belarusian State

A nationalized cinema

1919

For this time period, we have little reporting on what was going on in Belarusian movie theaters.

But we do know that the backlash again Bolshevism/Communism was just beginning in the west. One of the cinematic remnants of that time is Bolshevism on Trial, released in the U.S. in 1919. The story is about a “socialist agitator” who converts a well-meaning society woman to his views. She uses family money to purchase an island so they can continue the socialist experiment, to disastrous results. One of the characters in the film is an indigenous American, Saka, played by Luther Standing Bear. 1

Bolshevism on Trial poster, 1919.

Source: Mayflower Photoplay Company / Select Pictures Corporation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The film was also known as Red Republic and Shattered Dreams.2

In 1919, war and politics had an effect on administration and became fodder for future cinematic stories.

Belarusian historian Jan Zaprudnik wrote that on December 20, 1918, the sixth regional conference of the “Russian Communist Party (of Bolsheviks)” in Smolensk converted into the First Congress of the Communist Party of Belarus.3

Another Belarusian historian, Ivan S. Lubachko, wrote that on December 23, in Moscow, the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party opened a hearing on the question of Belarus and on the same day decided to create a socialist republic.4

Per Anders Rudling, who writes on Belarusian nationalism, wrote that week after the decision to create a Belarusian state was made. Rudling wrote that on December 25, Stalin announced the decision to create a Soviet Belarusian government.5 The Soviet government then directed the Northwestern Regional Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Belarusian territory was sometimes referred to as the North West Provinces) to call its sixth conference at Smolensk. At the first meeting, on December 30, the conference changed the name of the party to "Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Belarusia."6 Then, on December 31, that First Congress of the Belorussian Communist Party formed the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Revolutionary Government. 7

The first Belarusian communist detachment before departure from Petrograd to Minsk, 1919.

Source: https://library-mogilev.wixsite.com/1919-bssr

At that time, of course, the term in use was "Belorussia" or "Byelorussia." We are using the modern term of Belarus.

The Congress then elected a Central Executive Committee of 50 members, including Aleksandr Charviyakov and Joseph Adamovich.8 The two played key roles in arranging the production and release of Belgoskino’s first film, Forest Story. (more on that in an upcoming article on the film itself).

Aleksandr Charviyakov.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Enhanced by Google Gemini.

Joseph Adamovich.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

On New Year’s Day 1919, the first Soviet Belarusian state appeared, not as the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic, but as the Soviet Socialist Republic of Belarus (SSRB).9 It was proclaimed in Smolensk on January 1 and on January 8, its government moved to Minsk. The SSRB claimed jurisdiction over a large territory, covering roughly the same extent as the Belarusian National Republic.10

Flag of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Belarus, 1919.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

On the Recognition of the Independence of the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic.

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, having heard the report of the representatives of the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic on the situation in Belarus and the activities of Soviet power, resolves:

Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.11

Y. Sverdlov

An on line article by the National Library of Belarus states that, also in January 1919, there was a push to "nationalize" the cinema.12 Abram Galkin, who later became the first head of Belgsokino, was one of the people behind the push to nationalize the film industry in Vitebsk. Galkin, who may have been the Chairman of the Board of Artistic Enterprises of the Provincial Education at that time, proposed that the Vitebsk Department of Public Education take charge of the cinema business there.13 The article by the National Library of Belarus states not only that Vitebsk “nationalized” the cinema but that the program was successful.14 It distributed films not only in Vitebsk, but also in Mogilev and Smolensk provinces.

Vitebsk, beginning of the XX century.

Source: https://planetabelarus.by/publications/29-iyunya-osnovanie-vitebska/

The new Belarusian state that planned to nationalize the cinema lasted a total of 58 days15 On February 27, 1919 Russia created the ill-fated “Lithuanian-Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.”16

Historian David Wilson described its short life:

Lit-Bel forces fled gradually east. Their first capital was in Vilna, the second Minsk, the third Smolensk — a movement born out of necessity rather than historical symbolism. The Bolsheviks soon gave up on the idea.17

David Wilson

LitBel is the area outlined in blue.

Source: Renata3, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

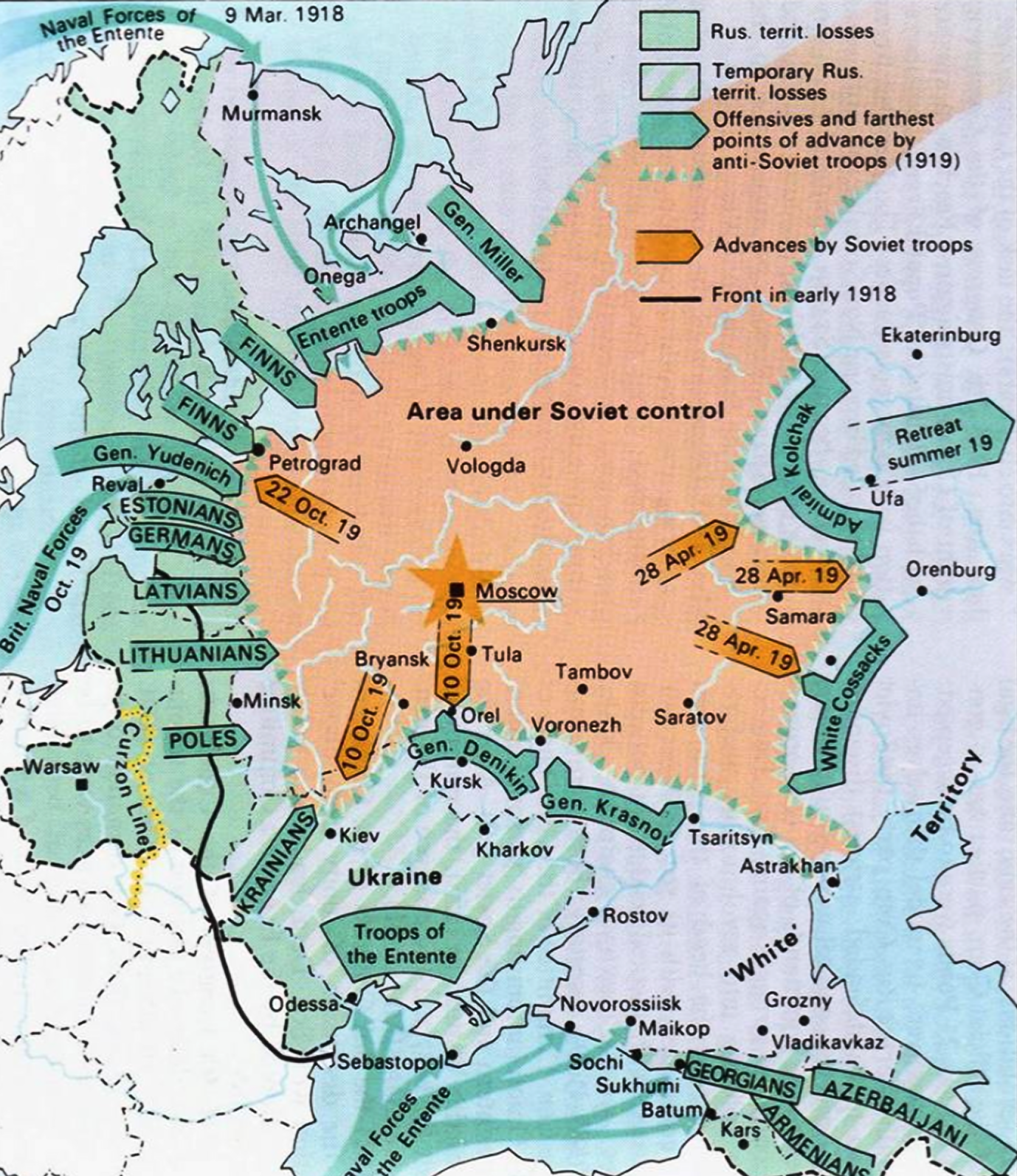

Soviet Russia quickly found itself fighting two wars. First, it was fighting a Civil War. The White Army, which supported the return of Tsarist rule, launched its first offensive in March 1919. The second conflict was the Soviet-Polish Border War (February 1919 – March 18, 1921).

The Soviets controlled the area in orange. The White Army and the Polish Army are shown with green labels. The area of the new SSRB is the small, gray area with the small dot indicating Minsk. The arrow marked “Poles” shows the pressure the Polish Army was putting on the new republic.

Source: https://www.techpedia.pl/index.php?str=tp&no=39016

The fighting did not stop the Bolsheviks from taking on the internal tasks to cement control. They had begun making agit-prop films as early as 1918 in order to spread their message. These filmswere sent by various means, including trains, to areas the Bolsheviks controlled. Film historian Richard Taylor described the situation:

Richard Taylor

The trains, not surprisingly, had revolutionary names, like Lenin and October Revolution. In March 1919, the Lenin train visited Minsk and Vitebsk. Between April 1919 and December 1920, the October Revolution train also came to Minsk19.

The website Incite has a page dedicated to the October Revolution train:

Incite’s photos come from early Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov, who also produced a newsreel called Cinema Week. The first 2 minutes of the following are moving pictures of an agit-prop train. Watch for a humorous moment about 1 minute in, when a large, oblivious Bolshevik walks between the camera and the crew loading the train. A much shorter and younger man who was part of the crew and showing off for the camera, pushes the surprised larger man out of the way.

Video of Dziga Verov’s Cinema Week. 1918 24 September.

Gomel Today reported in 2023 that, in June 1919, Mikhail Kalinin, who was President of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, rode an agit-prop train to Gomel to speak at a rally at the Theatre of Arts cinema. The theater was then renamed the First Soviet, and a few years later was named for Kalinin himself.20

Kalinin at the Gomel train station, 1919.

Source: Абецедарский Л.С., и друг. Abetsedarsky, L.S., and others История Белорусской ССР. The Story of the Byelorussian SSR В двух томах, т. 2/two volumes, vol. 2. (1961) Академия наук Белорусской ССР. /Academy of Sciences of the Belarus SSR. c. 140/p. 140.

1 Hanson, Patricia King and Gevinson, Alan, eds., "Bolshevism on Trial" *The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States, vol.F1: Feature Films, 1911-1920* Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988 p 176-78; https://catalog.afi.com/Film/17365-BOLSHEVISM-ONTRIAL?sid=64e13d8b-505e-4dba-a0be-f047d3695dc9&sr=11.768501&cp=1&pos=0

2 Ibid.

3 Zaprudnick, Jan Belarus, At a Crossroads in History Westview Press, 1993 p. 70.

4 Lubachko, Ivan S. Belorussia Under Soviet Rule, 1917-1957 University Press of Kentucky, 1972, p. 27.

5 Rudling, Per Anders The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906-1931 University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA 2014. p. 96.

6 Lubachko, p. 28, citing T. Gorbunov, Lenin i Stalin v bor'be za svobodu i nezavisimost' Belorusskogo naroda," / Lenin and Stalin in the struggle for freedom and independence of the Belarusian people Istoricheskii zhurnal, /Historical Journal nos. 2-3, 1944: 16; Rudling, p. 97 Shumeiko et al., Po vole naroda "239-240; Yekelchyk, Serhy Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation Oxford University Press, 2007, 241-242.

7 Lubachko, p. 28., citing Kastrychnik na Belarusi: zbornik artykulau i dakumentau/ Kastrychnik and Belarus: articles and documents Minsk, 1927, p. 123.

8 Lubachko, p. 30. Again citing Kastrychnik.

9 Rudling, p. 5.

10 Rudling, p. 97.

11 "Постановление Президиума ВЦИК о признании независимости Белорусской Социалистической Советской Республики. 5 февраля 1919 г."/"RESOLUTION of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee dated February 5, 1919 On the Recognition of the Independence of the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic" *ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ БИБЛИОТЕКА ИСТОРИЧЕСКИХ ДОКУМЕНТОВ/ELECTRONIC LIBRARY OF HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS* https://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/283753-postanovlenie-prezidiuma-vtsik-o-priznanii-nezavisimosti-belorusskoy-sotsialisticheskoy-sovetskoy-respubliki-5-fevralya-1919-g Accessed August 30, 2025.

12 Киноэхо из прошлого: что смотрели жители Беларуси сто лет назад/Cinematic Echo from the Past: What the inhabitants of Belarus saw a hundred years ago Национальная библиотека Беларуси/National Library of Belarus https://www.nlb.by/content/news/proekt-svideteli-epokhi-belarus-na-stranitsakh-gazet-100-letney-davnosti/kinoekho-iz-proshlogo-chto-smotreli-zhiteli-belarusi-sto-let-nazad/ Accessed March 12, 1920.

13 Шумилин, Д.А. и др./Shumilin, et al, eds. Временик Зубовского Института/Zubovsky Institute Times № 2(29)/No. 2(29) Министерство культуры Российской Федерации Российский институт истории искусств/Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Institute of Art History, St. Petersburg, 2020 p. 230.

14 Киноэхо из прошлого: что смотрели жители Беларуси сто лет назад/Cinematic Echo from the Past: What the inhabitants of Belarus saw a hundred years ago.

15 Rudling, p. 97.

16 Rudling, p. 98.

17 Wilson, Andrew Belarus, The Last European Dictatorship Yale University Press 2011. p. 99.

18 Taylor, Richard. A Medium for the Masses: Agitation in the Civil War, Soviet Studies Vol 22, NO. 4 (Apr. 1971), pp. 562-574, p.568.

19 Taylor, Richard The Politics of Soviet Cinema, 1917-1929 1979, 2008, Cambridge University Press., pp. 57-58.

20 «С пианистами в 30-х и с драками и поножовщиной в 80-х. Как появлялись, развивались, процветали и угасали гомельские кинотеатры – историческая статья от «Сильных новостей» /“With pianists in the 30s and with fights and stabbings in the 80s. How Gomel cinemas appeared, developed, flourished and died out” Гомель сегодня/Gomel Today 25 Jan 2023, https://vk.com/@gomeltoday-s-pianistami-v-30-h-i-s-drakami-i-ponozhovschinoi-v-80-h-kak Accessed 23 June 2025.