War and Revolution

1914-1917, Part I

1914

This site is meant to focus on the birth and growth of the cinema in Belarus. We cannot tell that story without discussion of World War I and the two Russian revolutions it engendered.

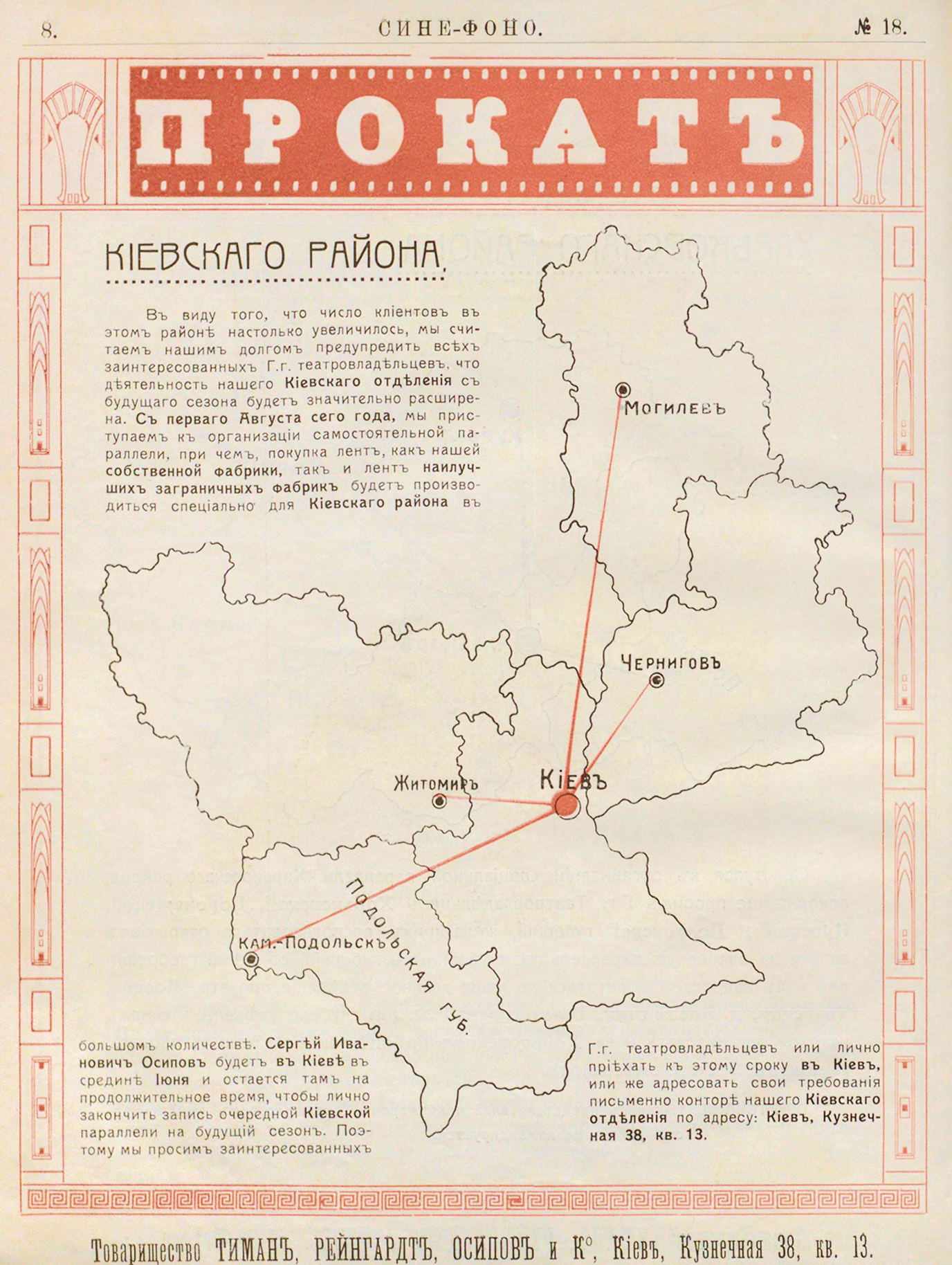

The film producers Thieman and Reinhardt published maps of their distribution networks in various issues of Cine-Phono. An ad on June 7, 1914 showed Vitebsk was served by the “Moscow Department.”1 Another, in the same issue showed Mogilev served by Kyiv.2

Thieman and Reinhardt published maps, 1914.

Source: Cine-Phono

Mogilev served by the Thieman and Reinhardt Kyiv Department, 1914.

Source: Cine-Phono

Vitebsk served by the Thieman and Reinhardt Moscow Department, 1914.

Source: Cine-Phono

Mogilev served by the Thieman and Reinhardt Kyiv Department, 1914.

Source: Cine-Phono

Just after World War I started, in October of 1914, Kine-Zhurnal reported that there were 5 theaters in Minsk: “Giant, Eden, Illusion, Lux, and a new grandiose cinema and theater, the Modern, [recently] was opened.”3

Later, Kine-Zhurnal also reported that Minsk theaters did their part once the fighting began: “It is planned to organize charity screenings in one evening in all electrotheaters, the entire collection from which will go to the benefit of the ruined inhabitants of the Kingdom of Poland.

The Directorate of Electrotheaters allows free admission to the sessions for wounded lower ranks and officers.”4

Another issue of Kine-Zhurnal reported that, by the end of 1914, Minsk theaters were doing good box office. The Eden screened The Girl from the Basement, described as “one of the rarely shown films from Russian life.” It was also reported that: “For the winter season, the Directorate acquired a number of action films from the military series; so far, the following films have been published: America-Europe by Air and Retreat of the Austrian Army in Galicia.”5

We have posters from America-Europe by Air, which was also known as The Sky Monster.

America-Europe by Air poster, 1914.

Source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0366167/mediaviewer/rm1103583744/?ref_=tt_ov_i

Sky Monster poster, 1914.

Source: ???

We have one short British newsreel with clips regarding how the war began.

Cine-Phono Magazine

Cine-Phono wrote that Gomel still had three theaters operating in 1915, the Theater of Arts, Moulin Rouge, and New Illusion. The report said the Theater of Arts is so popular, that its ability to seat 750 patrons at a showing was not enough. The Moulin Rouge put on “interesting programs, mainly of the Pinkerton genre.”18 (Allan Pinkerton was a well-known detective in the United States in the mid to late 1800s.)

There is at least one Pinkerton film still in existence. We found this copy at the Eyefilm Institute in the Netherlands.

Cine-Phon reported that the New Illusion was located near the railway. It did not run “flashy action films,” but an “interestingly selected program….that enjoys the sympathy of the station-side population.18

We can also direct you to this website, the European Film Gateway, which has a large collection of World War I newsreels from many countries.

We have been unable to find any Russian newsreels.

Kine-Zhurnal reported that theater owners in Mogilev were initially happy from the boost the war gave them. The population of the city increased with war refugees. “But along with these advantages, there is one ... very significant minus. What are we finally going to show to the public? After all, the public is demanding in the old way and does not know that there are almost no new films now. And so, willy-nilly, you have to work with old programs.” One of the movies was Samson and Delilah, shown at the Modern, from a company called Mizrah (Hebrew for “the east.”).6 Mizrah was based in Odessa.7

1915

Cine-Phono reported that, in early 1915, the Illusion, Modern, Eden, Giant, and the Lux were still operating in Minsk.8 On New Year’s Day, the local cinemas held a benefit for provisions for sick and elderly workers.9 Among the films being shown: The Passage of the Russian Troops through the San, Ruined Belgium, and The Treacherous Attack of the Turkish Fleet on the Black Sea Ports.10

Kine-Zhurnal reported that: “Pictures on the themes of the Russo-German War were a great success with the public.”11

From the fighting in the San area near Jaroslaw, illustration by F. Neumann, October 1914

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_San_river_%281914%29

We must also note that the war gave a great boost to the Russian film industry. Noted film historian Jay Leyda called it “an undisguised blessing to the Russian film industry.” Russian movie-makers were freed from foreign competition and were spurred to more intense and more efficient production.12 Before the war, most of the films shown on the Empire’s screens were imported. Vance Kepley, Jr., another well-known film historian, reported that, with the beginning of the war, Russia’s Western Front closed off almost all trade, including imports of western movies and movie making equipment.13 New films could not be imported. However, cinema owners did not destroy the old ones. They would be shown later, often many years after they were made, while the Soviet film industry, including the Belarusian film industry, struggled to get on its feet.

In early 1915 Kine-Zhurnal wrote highly of the Cathedral theater in Nezvizh: “The [premises] are distinguished by the luxury of detachment, comfort and an abundance of air, thanks to the high ceiling and spacious location of the rooms.”14 In September 1915, Kine-Zhurnal wrote that theater management donated the entire proceedings from one showing to the local Red Cross.15

Cine-Phono reported that the Orsha Illusion was closed for two months but reopened by March of 1915. It was now run by a Mr. Bogen.16

1 Cine-Phono, No. 18, June 7, 1914, p. 5.

2 Ibid, p. 8.

3 Kine-Zhurnal, Issues 19-20 (combined in one magazine), October 18, 1914, p.48.

4 Kine-Zhurnal, Issues 21-22 (combined in one magazine), November 20, 1914, p.69.

5 Kine-Zhurnal, Issues 21-22 (combined in one magazine), November 20, 1914, p.68.

6 Ibid, p. 68.

7 Cine-Phono, Issues 21-22, July 19, 1914, p. 33.

8 Cine-Phono, Issue 8, January 31, 1915, p. 91.

9 Ibid, p. 50.

10 Cine-Phono, Issues 6-7, January 10, 1915, p. 51.

11 Kine-Zhurnal, Issues 19-20, January 10, 1915, p.51.

12 Leyda, Jay Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film Allen & Unwin, LTD. London. 1960 p. 74.

13 Kepley, Jr., Vance. Soviet Cinema and State Control; Lenin’s Nationalization Decree Reconsidered. Journal of Film and Video, Summer 1990, Vo. 42, No. 2 (Summer 1990), pp. 4-14, p 6.

14 Cine-Phono, Issue 9, February 21, 1915, p. 51.

15 Kine-Zhurnal, Issues 17-18, September 17, 1915, pp. 103-104.

16 Cine-Phono, Issue 10, March 7, 1915, p. 58.

17 Ibid.

18Cine-Phono, Issue 18, July 18, 1915, p. 71.

19 Ibid.