The Movies in Communist Belarus

1921

As 1921 dawned, the Belarusian government continued to exert local control in many areas, including the cinema.

A Narkompros Journal from January–February 1921 lists a total of 125 cinema “programs,” of which 98 fell under the category “various content.” It did not say, by name, what films were shown. It did not say, by name, what films were shown. The journal says 5 cinemas were operating, all in Minsk: Red Star (formerly the Giant), International (formerly the Eden), Culture (formerly the Modern), Spartak (formerly the New Theater)4 and Commune (formerly the Illusion).5 The New Theater, which became the Spartak,6 had opened in 1916 and was still open in 1917,7 and, if we are to believe a picture dated 1918, was still open in 1918.

Minsk, Zakharjewskaja-Felicyjanauskaja street, 1919.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45606872

Vitold Ashmarin, then the editor of the newspaper Zvyezda (Star)8 was unhappy with the films shown by the cinemas. According to film scholar Natalie Ryabchikova, Ashmarin had been associated with Russian films from pre-revolutionary times.9 On February 15, 1921, Ashmarin wrote in his Zvezda article, “The Screens of Belarus,” that all that the Belarusian theaters are showing are “scraps of old, worn-out reels, meagerly supplied by the central authorities.”

Portrait (monotype) of Vitold Akhramovich by Anatoly Trapani, 1915.

Source: Vitold Akhramovich (Ashmarin) and Lev Kuleshov: At the inception of Russian film theory, 2021.

Ashmarin adds a rare instance confirming indigenous film production in Belarus. “The production of our own films has nearly ceased due to a shortage of film stock and chemicals.” Then Ashmarin finds someone to blame. “Our People's Commissariat of Education has a subdepartment for photo-cinematography, which currently distributes old reels to cinemas with great stinginess. Yet this subdepartment could evolve into a fully independent division, organize modest local production, contribute something to the center, and in return receive a greater quantity and better quality of film stock.10

A few days later, another article in Zvyezda reported on a meeting of many in the arts department. Their conclusions:

- To recognize the necessity of immediately taking all measures to expedite the organization of the film industry in Belarus, and

- To entrust the development of technical, financial, and other issues related to the said organization to the Department of Arts, specifically the photo-cinema sub-department.11

They had laid the ground for a more independent organization, Kinoresbel, which would start in June of 1922.

In response to the Zvyezda articles, Narkompros closed two cinemas in March 1921, although the documents we have do not say which ones.12

In August 1921, Lenin established the New Economic Policy, or NEP, which allowed businesspeople and some farmers to make profits. Lenin believed that the incentive of profit would spur an economic revival. History proved him right.

This poster was actually printed in 1930, after the NEP had been abandoned. It says, “From NEP Russia there will be Socialist Russia”.

Source: By WillZ8800 — Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Film historian Kristin Thompson describes what happened once the NEP was in place:

Kristin Thompson

Thompson and others note that those private firms had a profit incentive. Historian A.M. Yevtushenko writes that while some movies were shown for free in workers’ and army clubs, they tended to be documentaries or agit-prop. Private theaters showed more popular films and therefore could charge admission fees.14 There was not as much incentive for those private cinema owners to want to show anything but pre-revolutionary (or imported) dramas, comedies, or romances.

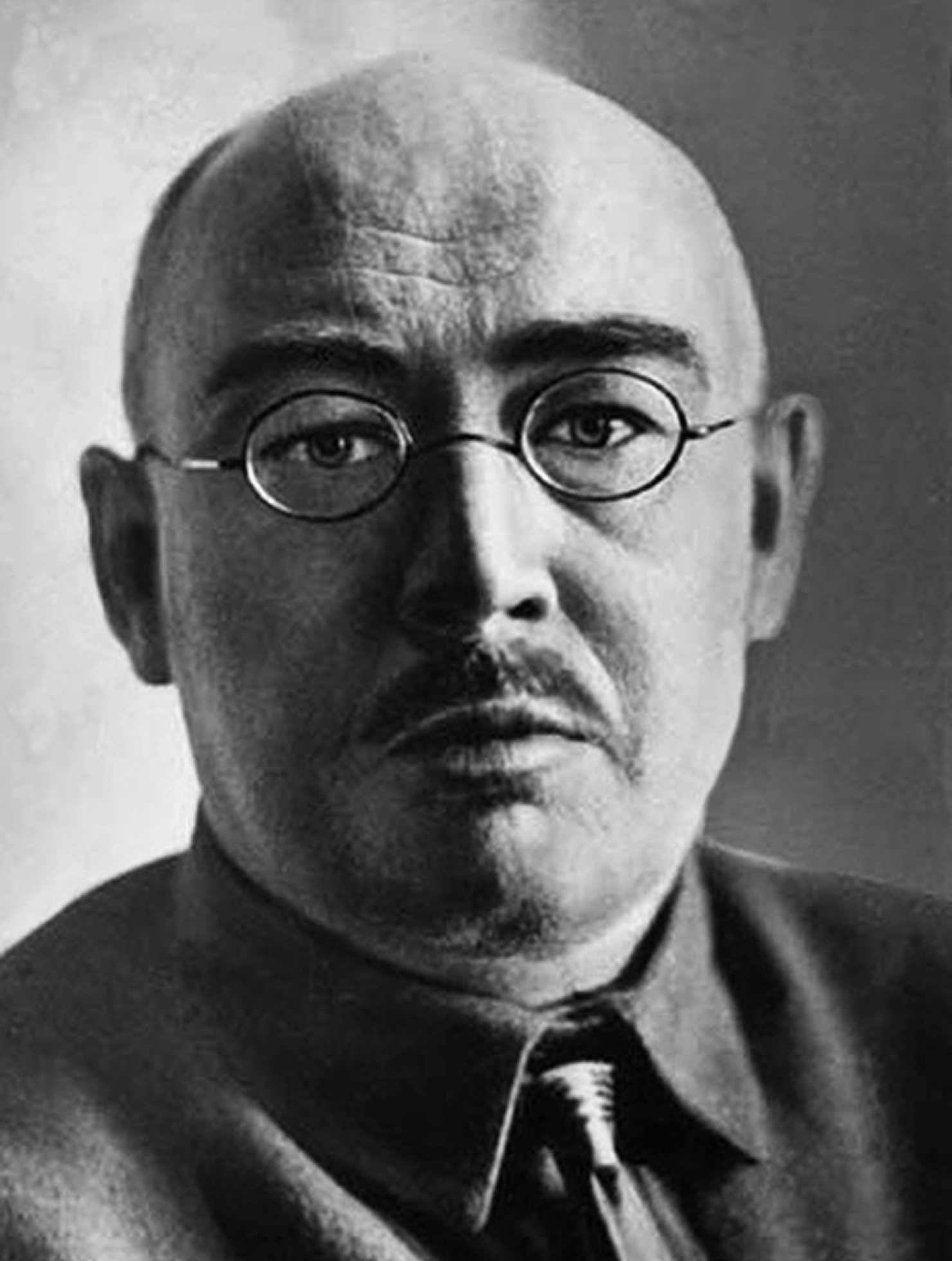

Soviet film historian Nikolai Lebedev writes that the Communist Party missed an opportunity to set Soviet cinema on a sound financial basis with the NEP.

Nikolai Lebedev

According to historian Peter Kenez, in late 1921 the first commercial cinema re-opened in Moscow. Soon there were many. With the NEP in place, theater owners had good financial reasons to sneak in dozens of features from outside of the country.16 Kenez also wrote that famous German films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), were shown in Moscow soon after they were made.17 It was this kind of thing that historian Nikolai Lebedev railed against. He wrote (about Moscow) "the Photo and Cinema Department of the People's Commissariat of Education, created under the conditions of war communism, and its local bodies proved powerless to cope with the market forces.” 18

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari/The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Decla-Bioscop AG

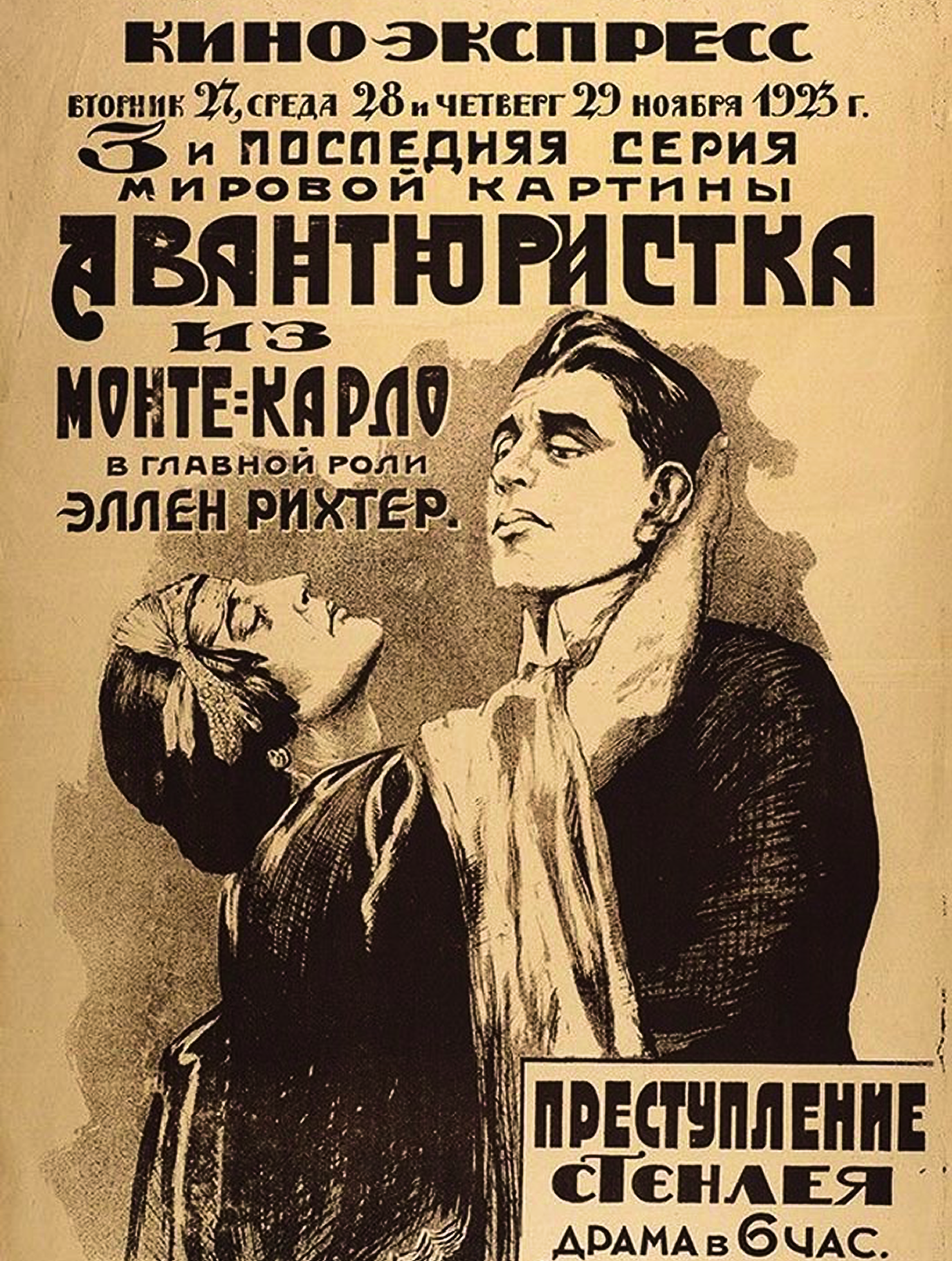

Lebedev named other films, too: “The windows of movie theaters are full of the titles of meaningless films of German, French, and American production: The Adventuress of Monte Carlo, The Mystery of the Egyptian Night, The House of Hate, The Bride of the Sun, In the Slums of Paris, The Five Rothschilds, In the Claws of the Beast, etc., etc.” 19

The Adventuress of Monte Carlo, 1921.

Source: https://humus.livejournal.com/5597479.html

House of Hate, 1918.

Source: by Unknown author, Internet Archive, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

On December 17, 1920, the Belarusian constitution had been amended to create the Central Executive Committee (Ts.I.K.) and the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom). Aleksandr Charviyakov was elected chairman of both the Ts.I.K. and the Sovnarkom.1 Vilhem Knorin was named First Secretary of the Central Bureau of the Belorussian Communist Party.2 Vsevolod Ihnatouski was head of the People’s Commissariat of Education, known as the Narkompros, which controlled cinema through its Arts Department and sub-division Photo-Kino Department.3

Vilhelm Knorin, 1928.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Vsevolod Ihnatouski.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

1 Lubachko, Ivan S. Belorussia Under Soviet Rule, 1917-1957, U of Kentucky P, 1971, p. 49. Quoting Ocherki po istorii gosudarstva i prava Belorusskoi SSR [Essays on the history of the state and law of the Belarusian SSR], Minsk, 1958, p. 41; Bol'shaia sovetskaia entsiklopediia [Great Russian Encyclopedia], 1st ed., vol. 61, Moscow, 1929-1948, p. 195; Ocherki po istorii [Outline on History], p. 41; S’ezdy Sovetov SSR [Congress of Soviets], vol. 2, pp. 251-252.

2 Lubachko, p. 50.

3 “Vsevolod Makarovich Ignatovsky”. Faculty History of the BSU https://hist.bsu.by/en/honorary-callery-of-the-faculty-of-history/7405-vsevolod-makarovich-ignatovsky-19-04-1881-04-02-1931.html#gsc.tab=0 Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

4 Shkola i kul’tura Sovetskoy Belorussii [School and Culture of Soviet Belorussia]. Natsional’naya biblioteka Belarusi [National Library of Belarus]. Accessed 25 Oct. 2025.

5 Marakov, Leanid (Леанід Маракоў), Hałoŭnaja vulica Minska, 1880–1940 hh [The Main Street of Minsk, 1880–1940]. Vol. 1, Mastackaja litaratura, 2012, p. 14.

6 Volozhinsky, Vladimir (Воложинский, Владимир). “Gde v Minske byl pervyy kinoteatr i o chem byli pervye minskie fil'my?” [“Where Was the First Cinema in Minsk and What Were the First Minsk Films About?”]. Tut.by, 17 Apr. 2013. Archived at Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20180401172506/https://news.tut.by/culture/344182.html Accessed 31 July 2025.

7 Marakov, p. 8.

8 “O chem prosil Stalina odin iz osnovateley BelTA pered smert'yu?” [What Did One of BelTA's Founders Ask Stalin for Before His Death?]. Minsk Novosti [Minsk News], 7 May 2019. https://minsknews.by/o-chem-prosil-stalina-odin-iz-osnovateley-belta-pered-smertyu/ Accessed 27 Sept. 2025.

9 Ryabchikova, N. S. (Рябчикова, Н. С.). “Vitold Akhramovich (Ashmarin) i Lev Kuleshov: u istokov russkoy kinoteorii” [Vitold Akhramovich (Ashmarin) and Lev Kuleshov: At the Inception of Russian Film Theory]. Teatr. Zhivopis’. Kino. Muzyka [Theatre. Fine Arts. Cinema. Music], no. 3, 2021, pp. 61–79. DOI: 10.35852/2588-0144-2021-3-61-79; Ryabchikova, N. S. “Rannie kinoopyty Vitol'da Akhramovicha, 1913–1918 gg.” [Early Film Work of Vitold Akhramovich, 1913–1918]. Teatr. Zhivopis’. Kino. Muzyka, no. 2, 2022, pp. 81–103. DOI: 10.35852/2588-0144-2022-2-81-103.

10 Ashmarin, V. (Ашмарин, В.). “Ekrany Belorussii” [The Screens of Belarus]. Zvezda [Star], no. 37 (721), 15 Feb. 1921. Prezidentskaya biblioteka Respubliki Belarus [Presidential Library of Belarus].

11 “Kino-promyshlennost' Belorussii” [The Film Industry of Belarus]. Zvezda [Star], no. 42 (726), 20 Feb. 1921. Prezidentskaya biblioteka Respubliki Belarus [Presidential Library of Belarus].

12 “Protokol” [Protocol]. Fond 42, inv. 1, file 76, fols. 42-42b. Natsional’nyi arkhiv Respubliki Belarus [National Archives of the Republic of Belarus], Minsk.

13 Thompson, Kristin. “Government Policies and Practical Necessities in the Soviet Cinema of the 1920s.” Red Screen: Politics, Society, Art in Soviet Cinema, edited by Anna Lawton, Routledge, 1992.

14 Yevtushenko, A. M. (Евтушенко, А. М.). “Russkoe kino perioda NEPa v aspekte gosudarstvennogo i partiynogo stroitel'stva” [“Russian Cinema of the NEP Period in the Aspect of State and Party Building”]. Vector of TSU Science, https://www.vektornaukitech.ru/jour/article/view/516, p. 112. Accessed 15 Mar. 2025.

15 Lebedev, Nikolai (Лебедев, Николай). Kino: Ego kratkaya istoriya, ego vozmozhnosti, ego stroitel’stvo v sovetskom gosudarstve [Cinema: Its Short History, Its Possibilities, Its Construction in the Soviet State]. Moscow, State Publishers, 1924, p. 97. Quoted in Kristin Thompson, “Government Policies and Practical Necessities in the Soviet Cinema of the 1920s,” Red Screen, Routledge, 1992, pp. 49–63.

16 Kenez, Peter Cinema and Soviet Society: From the Revolution to the Death of Stalin, I.B. Tauris, 2000, p. 35.

17 Kenez, p. 35.

18 Lebedev, Nikolai (Лебедев, Николай). Ocherki istorii sovetskogo kino [Essays on the History of Soviet Cinema]. Iskusstvo [Art Publishing House], 1965.

19 Lebedev, p. 146.