Richard Eduardovich Stremer — The First Film Magnate in Belarus

Nine years after Katin began showing French films in Vitebsk, Richard Eduardovich Stremer opened the first known permanent theater in Minsk.

As we wrote last time, the Lumière brothers showed their Cinématographe at the Nizhny Novgorod Fair in 1896.1 Richard Stremer purchased one, and some films, too.2 Then he went on tour to the western provinces of the Russian Empire.

Nizhny Novgorod, view of the Main Fair House

.

Source: By Maxim Petrovich Dmitriev http://chronograph.livejournal.com/180282.html

Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45650336

At one time, Stremer had theaters in St. Petersburg, Kiev, Riga, Lodz, Kiev, Chernigov, Uman, Mitava,3 Vilna, Pyatigorsk,4 Rostov-on-Don.5

In 1900, Stremer came to Minsk and rented an empty room in the Rakovshchik house on Zakharyevskaya Street (now Independence Prospect).6 At first, it was just a "Magic Lantern" show, in which a powerful lamp directed light through slides to project a still picture onto a wall. He probably also showed moving pictures in this room, but we have not seen reporting that he did.

Minsk, Zakharyevskaya street, end of the XIX century.

Source: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Захарьевская_улица_(Минск)

In February 1904, the same year the Russo-Japanese War began, two major French filmmakers, Pathé Freres and Gaumont, opened offices in Russia.7 In 1905, the Tsar eased restrictions throughout the empire. Belarusians began publishing newspapers and books in their own language and founded the newspaper Nasha Niva.8

Books in Belarusian language from the publishing house “Zahlianie sonca u našje vakonca”, 1906, 1910, 1913.

Source: https://kamunikat.org

In 1907, the Illusion Electrotheater opened in Minsk at the corner of Zakharyevskaya and Petropavlovskaya streets. (Click to see when it was referred to as the Parisian Illusion) Was this Stremer’s theater? One article said yes.9 Theaters were often called “illusions” because the pictures gave the “illusion” of life. On December 1, 1907 Cine-Phono referred to an Illusion in Minsk, but it is unclear if that is actually the name of theater.10

Minsk 1903 M. Epstein, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Source: https://garystockbridge617.getarchive.net/media/minsk-m-epstein-aa7b00

On March 1, 1908, Cine-Phono referred to Stremer’s theater as the Electro-biograph not the Illusion.11 Electro-biograph was another description of a cinema, and not necessarily a name. We have not heard of a second Stremer theater in Minsk. Yet another writer asserted that Stremer’s theater was the Eden12 Cine-Phono, however, reported that the Eden “was next to Stremer."13 It also reported that Minsk had two other theaters, the Illusion and the Modern.14

Pathé Frères movie projector, about 1910.

Source: Nordisk familjebok, https://runeberg.org/nfbn/kinema.jpg Wikimedia Commons

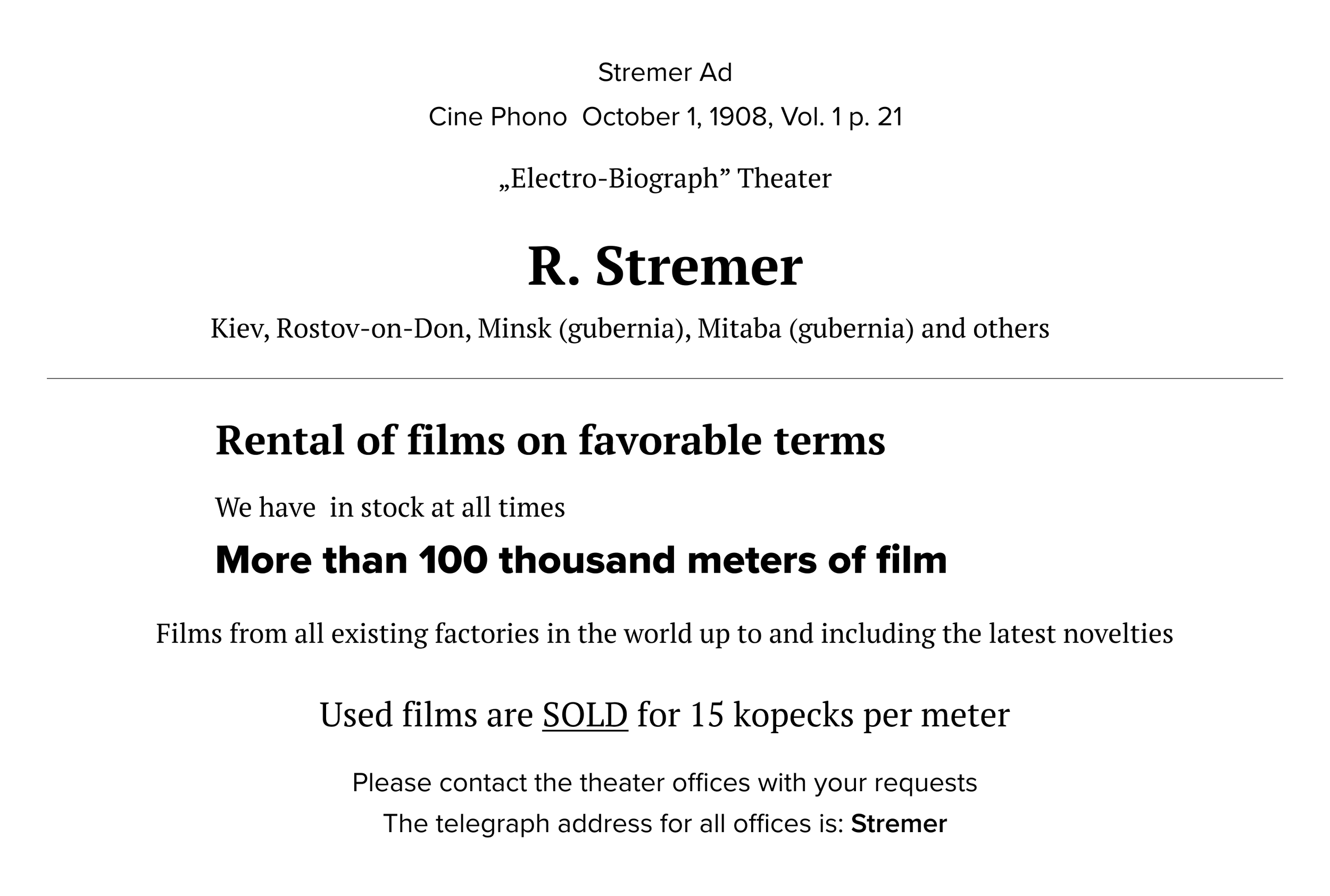

Stremer, too, referred to his theater as the Electro-Biograph in an ad in Cine-Phono in late 1908. He was also a film distributor and seller, according to his ad, with “thousands of meters” of film.15

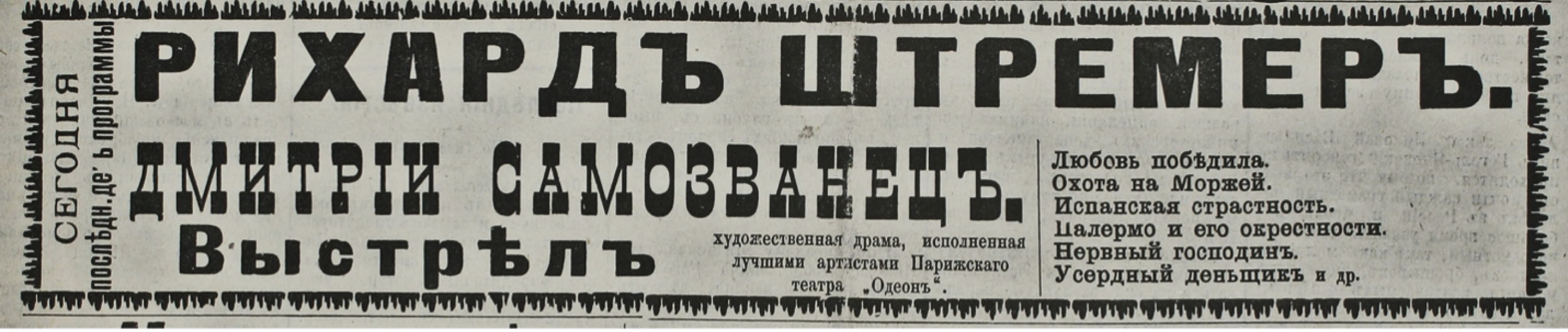

It was Stremer’s name that drew the audience. On March 20, 1909, he placed an ad in the newspaper Minsk Echo. It showed his name, not the theater’s. On the screen were Dmitry the Pretender, which would be a story known to everyone in the Russian Empire, Love is Victorious and several short films.

Minsk Echo, March 20, 1909.

By 1909, Stremer had theaters in Minsk, Gomel, and Mogilev.16 Stremer, his wife, and the Gomel theater (see more about theaters in Gomel here) were named in the novel The Whirlwind by L.V. Miranova. In that story, the main character goes to the Illusion movie theater in Gomel and watches the performer Miss Volta, who appears before the audience in front of her and in front of a Tesla coil (probably) sending out lightning bolts behind her.

A real Miss Volta astounded the audience by channeling electricity through her fingertips to light lamps and cigars.17

New World Attraction Number!

Original! All Competitors! Original!

For the first time in Russia.

Miss Lucia Volta is 18 years old.

Works at a voltage of over 500,000 volts: thanks to which she carries out amazing experiments such as from her hands, legs, back, lamps, light up, torches, cigars, etc.

We live in a world of electricity and therefore electrical miracles are not fairy tales.

Foreign and Russian certificates of the Imperial Technical Societies serve as proof of the above.

These sessions are served by the city current and are possible from any stage.

For detailed information, please contact T.E.Tenzel,

Bioscope G.K. Zailer, Ekaterinoslav 18

Miss Volta.

A living electric battery.

1 Гинзбург С./Ginzburg, S.Кинематография доререволюционной России/Cinematography of Pre-Revolutionary Russia Издательство Искусство/Art Publishing House 1963, p. 17.)

2 Пилюгин, А. Ю./Pilugin, A. YuРихард Штремер — Человек, Открывший Ростовцам Синематограф/Richard Stremer - The Man Who Opened Cinematography to Rostovites Ростовский областной музей краеведения/Rostov Regional Museum of Local Lore, 2018, p. 2. https://www.academia.edu/36912293/Рихард_Штремер_человек_открывший_ростовцам_синематограф

3 Ibid.

4 "первая электробиография"/"First Electrobiograph"Топонимика Пятигорска»/Toponymy of Pyatigorsk. Библиотека КМВ/KMV Library http://lib.kmv.ru/projects/toponim/toponimika.php?rub=78 Accessed 31 July 2025

5 Ханжонков, Александр/Khanzhonkov, Alexander Первые годы русской кинопромышленности, Издательство/First Years of the Russian Cinema IndustryИздательство Искуство/Art Publishing House 1987

6 Воложинский, Владимир/Volozhinsky, Vladimire «Где в Минске был первый кинотеатр и о чем были первые минские фильмы?»/"Where Was the First Cinema in Minsk and What Were the First Minsk Films About?". Tut.by 17 Apr. 2013. Archived at Internet Archive. Accessed 31 July 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20180401172506/https://news.tut.by/culture/344182.html

7 Гинзбург [Ginzburg], p. 28. Лихачев, Борис С./Likachev, Boris C. Кинематография в России (1896-1926)/Cinematography in Russia (1896-1926) Академия/Academia 1927, p 29.

8 Marples, David R. Belarus, a Denationalized Nation, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1999, p. 2.

9 Воложинский [Volozhinsky]

10 Cine-Phono, No. 3, 07 Dec. 1907, p. 11.

11 Cine-Phono, No. 8, 1 March 1908, p. 10.

12 Пилюгин [Pilyugin], p. 118.

13 Cine-Phono, No. 2 15 Oct. 1909, p. 13.

14 Cine-Phono, No. 7, 15 Feb. 1907, p. 11.

15 Cine-Phono, No. 1, 1 Oct. 1908, p. 21

16 «Кинематография»/"Cinematography" Могилевский губернский журнал «Ведомости»/Mogilev Provincial Journal "News", 20 March 1909, p. 13

17 Youngblood, Denise J. The Magic Mirror. Moviemaking in Russia, 1908-1918 The University of Wisconsin Press 1999 p. 65, citing an advertisement Cine-Phono No. 8, 15 Jan. 1910.

18 Cine-Phono No. 8, 15 Jan. 1910, p. 24.