War and Revolution

1915-1917,

Part II

1915

After the war began in August of 1914, the fortunes of war quickly turned against the Russian Empire. Historian Lizavetta Kasmach wrote about how the Germans overwhelmed Russian forces.

Lizaveta Kasmach

Map of the Ober-Ost. The areas marked Grodno, Wasilishchki, Planty, Ost, Alekszyce, Wolkowysk, and Swislocz roughly make up a good part of Western Belarus today.

Source: XrysD, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Map of the Ober-Ost area from a German propaganda poster from World War I.

Source: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostrubel

The new Eden theater opened in Grodno a year after the beginning of the war. The story is well told online by Vladmir Severin. He wrote that Sergei Monastyrsky had hoped to build and open the Eden in Grodno in May of 1914. Various issues, then the war delayed the opening until November of 1915, after the Germans had already taken the city. Monastyrsky lost control of the theater after the war and after Grodno became part of Poland. The building survived and today is known as the Red Star.2

After Grodno and Brest-Litovsk were incorporated into the Ober Ost, they nearly disappeared from Russian/Belarusian cinematic reporting for the years 1915-1939. Vilna, of course, had long been the cultural and political center of Belarusian culture. The German takeover was the beginning of a separation that was made permanent with the establishment of Lithuania.

1916

We could find no reporting on films or theaters in Belarusian territory in 1916. The issues of Cine-Phono were combined, meaning sometimes two issues were consolidated to be printed together but there was no mention of the status of cinema in Belarusian territory. For Kine-Zhurnal, sometimes more than two issues were consolidated. There was still plenty of advertising in these consolidated issues. One may wonder whether that meant the movies were more popular than ever, or whether producers and distributors were desperate to have their product put on the screen. It may also have been a struggle to get the physical resources (paper and ink) to publish.

On July 31, 1916 in Cine-Phono, one could see that Thieman and Reinhardt were still trying to serve Mogilev from Kyiv.

Mogilev served by the Thieman and Reinhardt Kyiv Department, 1914.

Source: Cine-Phono, No. 17-18, 31 July 1916, p. 150.

1917

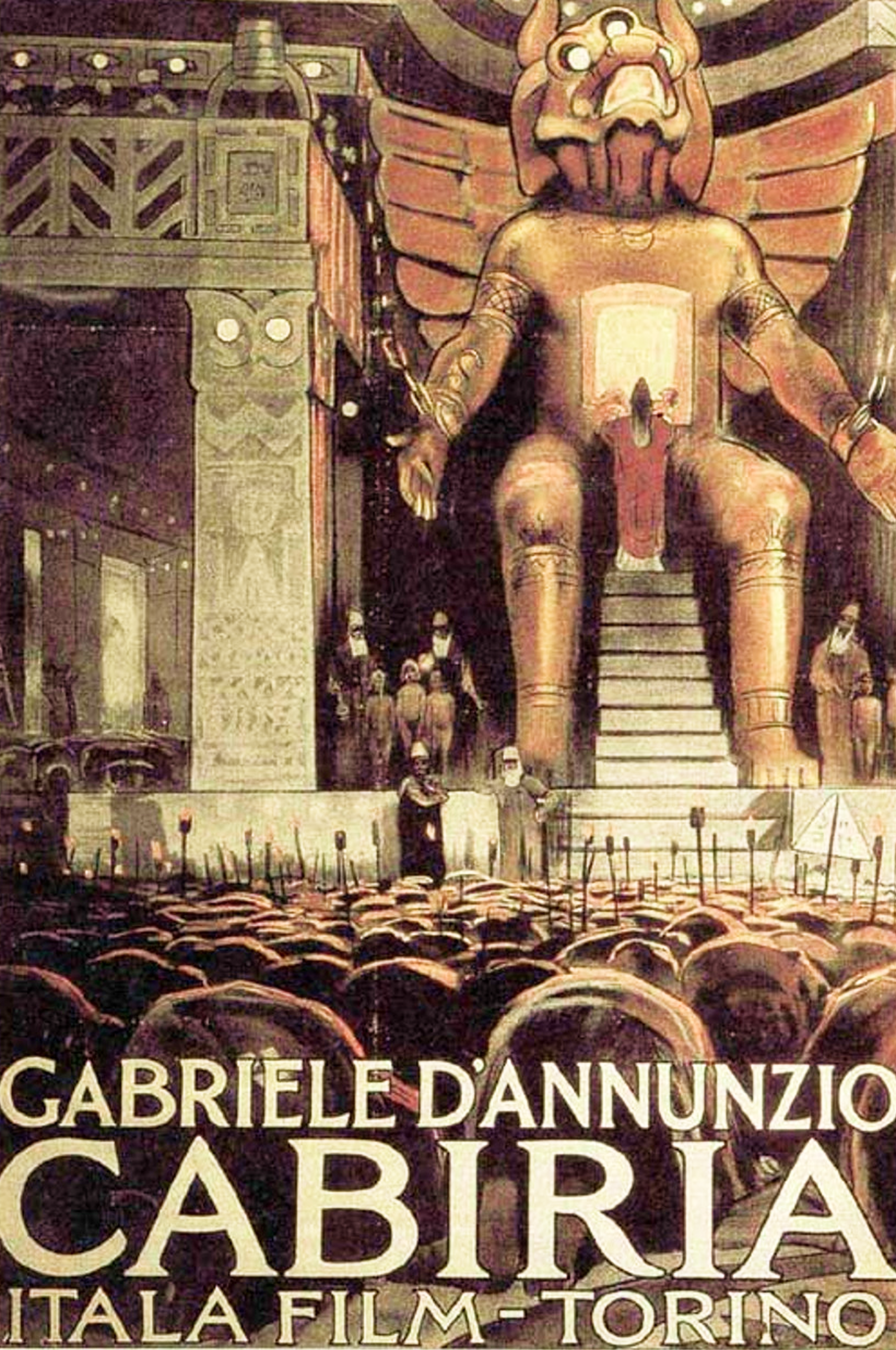

In January of 1917, just before the first Russian revolution, which resulted in the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, Cine-Phono reported that “The Minsk departments of the Russian Society for the Preservation of People's Health propose to organize a number of mobile cinematography (portable projectors, Eds.) in the province. Cinematographers will travel to villages and villages and make pictures, especially in terms of hygiene and other things.”3 In Vitebsk, they showed the smash Italian hit Cabiria, reported as “an unprecedented success.”4

Poster from the film Cabiria.

Source: https://www.posterazzi.com/cabiria-movie-poster-print-11-x-17-item-movei6569/?srsltid=AfmBOoqTio66vZc_Je8qkhz-a0bZR7dv4R3hdCQotonY6TIGKh5M2hum

Poster from the film Cabiria.

Source: N. Morgello, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In March 1917, after the revolution, Cine-Phono reported only that the Kino-Arts and the Arttheater were still operating in Vitebsk. “…the picture ‘He Died, Poor Fellow, in a Military Hospital’ was held for 13 days in a row…”5 Cine-Phono wrote:

Cine-Phono Magazine

The British Film Institute has a number of newsreels on Russia’s involvement in the war and also on both revolutions of 1917.

In March, film-makers from around the lands of the former Imperial Russia met in Moscow to try to form a “Union of National Cinematography.” The effort failed, and smaller unions sprang up around those same lands, including Minsk. Unfortunately, we have no other details on the union.7

The online journal Gomel News in 2017 reported that: “In 1917, there were already 56 private cinemas in Belarus.”8

Kine-Zhurnal was cheery in June 1917, when it wrote of a film it called The Robber of Other People's Happiness,9 “In the incomparable film, The Robber of Other People's Happiness, and with her characteristic skill she positively charmed the Vitebsk audience, which willingly visited the picture with her participation,” and “Despite the fact that Henny Porten had been absent from the screen for a long time and the audience began to forget her, she was rightly christened: the "Russian Kholodnaya."10 It turns out that a number of German films continued to be shown in Russia during the war, with the exhibitors claiming the films were American, Dutch, French of Danish.11 The Russian distributor R. Persky was notorious for passing off German films as Danish. Kine-Zhurnal was his publication.12

Henny Porten Poster.

Source: Kine-Zhurnal Magazine, No. 16, 24 Aug. 1913,

p. 110.

Henny Porten, 1915. Von Tekniska museet, CC BY 2.0.

Source: Wikimedia Commons 134748925.

Henny Portern and Emil Jannings in Anne Boelyn.

The end of October 1917 would bring significant changes to Russia, no longer an empire, and then under control of the Provisional Government. With the Bolshevik Revolution, Belarusian Nationalists saw a chance to push for a Belarusian state. Through it all, Belarusians continued to go to the movies. “The business” in Belarusian territory seemed to be like it was anywhere else, “the show must go on.” And it did.

The website Seventeen Moments in Soviet History has newsreel footage from just after the second revolution.

Newsreel footage from the days immediately following the October take-over, including clips from the Winter Palace, Bolshevik headquarters at the Smolny Institute, and selected revolutionary leaders, 1917.

Source: https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/bolsheviks-seize-power/the-october-revolution-in-petrograd-1917/the-october-revolution-in-petrograd-1917/

For those unfamiliar with why the revolution is called the October Revolution in Russia and other former Soviet countries, and the November Revolution in the West, it is because the Russian calendar (the Eastern Orthodox calendar, which is based on the Justinian calendar) was about two weeks behind the Western Gregorian calendar until February 1918, when the Bolsheviks instituted the Gregorian calendar for Russia.

1 Kasmach, Lizaveta, “Forgotten occupation: Germans and Belarusians in the lands of Ober Ost (1915–17)” Canadian Slavonic Papers/Revue Canadienne Des Slavistes, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2016, pp. 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2016.1238613

2 Северин, Владимир/Severin, Vladimir «Гори, свети, моя «Звезда»!» Старейшему кинотеатру Гродно — более 100 лет/“Burn, shine, my ‘Star!’ The oldest cinema in Grodno is over 100 years old.” Аргументы и факты в Беларуси/Arguments and facts in Belarus 2 Nov. 2024. www//aif.by/timefree/history/gori_siyay_moya_zvezda_samomu_staromu_kinoteatru_grodno_bolee_100_let Accessed 8 March 2025.

3 Cine-Phono, Nos. 17-18 (combined in one magazine), January 1917, p.70.

4 Kine-Zhurnal, Nos. 1-2 (combined in one magazine), 27 January 1917, p.87.

5 Cine-Phonol, Issues 11-12 (combined in one magazine), March 1917, p.91.

6 There seem to be many versions of film’s name. Poor Man Died in a Military Hospital, Poor Fellow Died in a Military Hospital, and The Soldier’s Life. The film was released in October 1916 by the Skobolev Committee. A. Ivonin directed and Nikolai Saltykov starred. hhttps://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/movie/empire/15216/annot/

7 Гращенкова, И.Н./Grashchenkova, I.N. Кино Серебряного века Русский кинематограф 10-х годов и Кинематограф Русского послеоктябрьского зарубежья 20-х годов/Cinema of the Silver Age, Russian Cinema of the 10s, Cinema of the 20s of the Russians abroad post-October, Министерство культуры Российской Федерации/Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation 2005 p. 130.

8 «Кино для масс: интересные факты из истории кинематографа в Гомеле»/“Cinema for the masses: interesting facts from the history of cinema in Gomel,” Гомельские ведомости Gomel News 15 June 2017. https://newsgomel.by/archive_news/society/13103--kinoiskusstvo---v-massy-lyubopytnye-fakty-iz-istorii-kinoprokatnogo-dela-v-gomele_27787.html Accessed 10 March 2025.

9 Portern’s filmography does not list any film entitled simply, The Robber. However, there is a film, Die Räuberbraut (The Robber Bride) from 1915 and this is probably the film to which the article refers.

10 Kine-Zhurnal, Nos. 11-16, 30 June 1917, p. 121. The article actually says: “The Russian Kholodnaya.” But of course, Vera Kholodnaya was already the “Russian Kholodnaya” and Henny Porten was described as a Danish actress. The writer probably meant, the “Danish Kholodnaya.” Porten was actually German, not Danish, but one can understand a German actress may not have been too popular during the war.

11 Leyda, Jay. Kino. A History of the Russian and Soviet Film, George Allen and Unwin, 1960, p. 76.

12 Гинзберг, С./Ginzberg, S. Кинематография дореволюционной России/Cinematography of Pre-Revolutionary Russia Издательство «Искусство»/Art Publishing House 1963, p. 156, fn. 115.