Kinoresbel Begins Work and Is Attacked

The new film organization for Belarus, Kinoresbel, officially opened for business on June 1, 1922. Its enemies quickly went after it.

It was reported in the June 1 edition of Minsk newspaper Zvezda that Kinoresbel had obtained jurisdiction over the cinemas which had previously been under the jurisdiction of the Glavpolitprosvet 1 (the Directorate of Political Education). This was done over the objections of Anton Balitsky, deputy head of the Narkompros (People’s Commissariat of Education).2

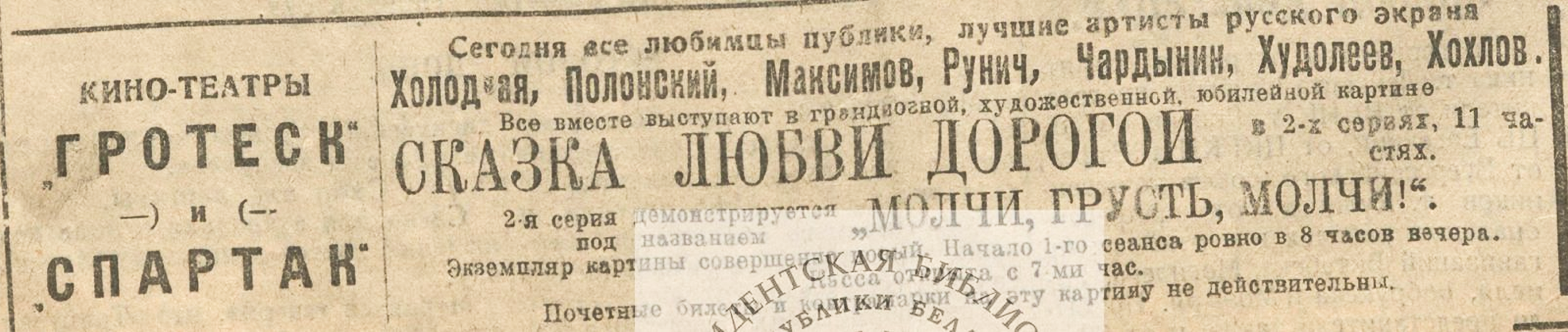

Two cinemas that were not transferred to Kinoresbel were the Spartak (formerly the New Theater, which the Red Army had leased, see here) and one with a the very un-communist name of Grotesque. Archival documents show that the Grotesque occupied the space of Stremer’s 1907 cinema in the Rakovshchik house, which had been rebuilt the fire of 1909 (more about the fire here) In 1921, the Terevsat theater was opened there, with room for 300 people.3

Archival documents also show that by March of 1922, the Red Army had turned it into a cinema.4 Zvezda newspaper ads for June 11, 1922, show the theaters were screening Silence, Sadness, Be Silent. (see more here).

Still of the cast members from the Silence, Sadness, Silence, 1918.

Source: http://www.everjazz.ru/playbill/item/3034/

Zvezda June 11, 1922.

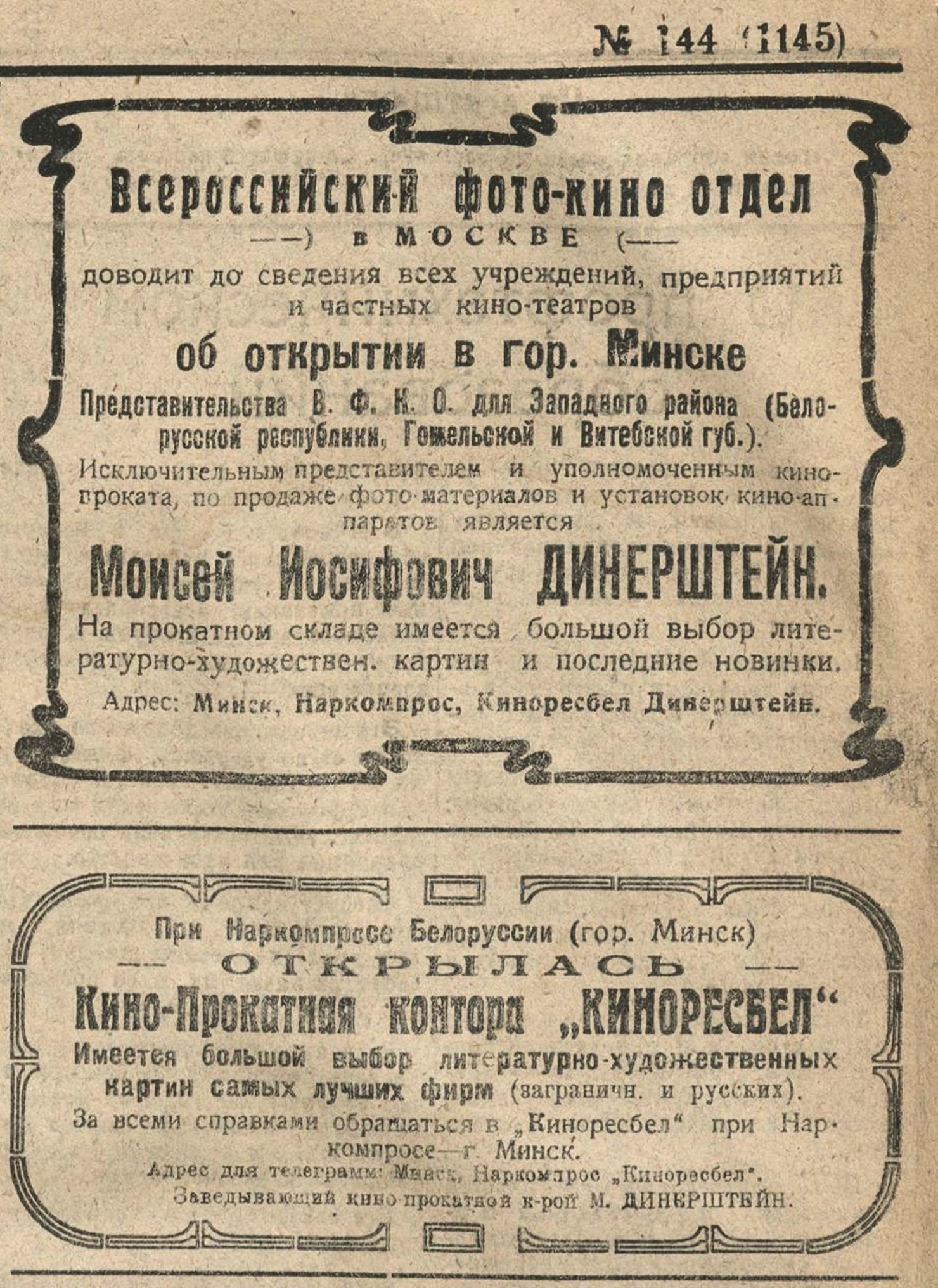

On June 20, 1922, Zvezda ran two advertisements announcing the opening of Kinoresbel.5

Zvezda, June 20, 1922.

These two ads say slightly different things about the opening of Kinoresbel.

The first, larger ad, says “The Belarusian Photo-Cinema office in Moscow brings to the attention of all institutions, enterprises and private cinemas, the opening in Minsk of the Belarusian Photo Kino Office for the Western region (The Belarusian republic, Gomel and Vitebsk governates).” It also announces Moise Dinershtein as the head of the organization.

The second, smaller one, says “Narkompros (People’s Commissariat of Education) in Belarus (city of Minsk) is opening the cinema rental office ‘Kinoresbel.’”

On July 14, an article in Zvezda went after Samuel Rakhlin, the deputy head of Kinoresbel. The article strongly criticized a play he had written, In the Steppe of Hunger.6 As the Communist Party organ, Zvezda was not printing a strong criticism of Rakhlin by accident. He should have been considered warned.

There were two other notable reports the same day. In one, it was reported that Kinoresbel had entered into an agreement with Vneshtorg (Ministerstvo vneshnei torgovli) the Ministry of Foreign Trade of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.7

The second Zvezda report said that the Giant cinema in Minsk, still called by that old name, and not its new one (Red Star), would be renovated at a cost of 5 million rubles.8

Cinema Red Star, Minsk, 1930.

Source: Zvezda newspaper, 12.11.1930. Siarhiej Marcinovic, electronic archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cinema Red Star, Minsk, 1930. AI Gemini enhanced.

Then the big blow came. In July of 1922, just a month after Kinoresbel took the reins, Narodny Kommissariat Raboche-Krest'yanskoy Inspektsii of Belarus (the Workers and Peasants Inspection Committee), or Rabkrin, began an audit.

The audit covered January 1 to June 1, 1922, when the Photo-Cinema Department was running things, and then from June 1 to July 15, after Kinoresbel took over.

The audit, led by A.N. Saikovsky, inadvertently highlighted the conflict between the effort to comply with Lenin’s New Economic Program (i.e., to pay its own way) and the desire of more hard-core Communists to use the cinema for “education.”

The audit excoriated Kinoresbel for the choices of movies shown and for poor record-keeping. The audit says that showing films in Bobruisk and Gomel through a contractor, Marcus Mnushkin, “yielded 7,277 rubles” but that a lack of documentation made it impossible to tell whether there was a profit. (More on Mnushkin here and here)

The report also says that films were obtained from Mark Aronov, who had worked in cinema before the revolution (see more here and here), from the All Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Photo Committee (VUFKU), from someone named Sokolovsky,9 and from a Muscovite named Bystritsky.10 The inference in all cases was that the material was unsuitable or worse.

Cinema Red Star, Minsk, 1937.

Source: NARB, fond 4P, q.1, ref. 15656, apk. 46. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cinema Red Star, Minsk, 1937. AI Gemini enhanced.

The audit refers to the Minsk theaters but calls them by their old names. It said the Giant (now re-named Red Star) and Eden (now re-named International) showed “artistic” films but never says what “artistic” means. The audit adds that the Modern (now re-named Culture), also in Minsk, showed films of a “sensational-detective character.”

The films complained about in the audit are all or nearly all from before the revolution. We have not been able to track down Suffering of Love (described in the report as a comedy), The Gambler11 (or Cardsharp), or Atonement of Blood. One of the films we were able to find was A Nest of Nobles. Another English title, per IMDB, is Dionysus's Anger.12) One of the biggest problem the auditors found with this film was that it was not complete. Kinoresbel had only 5 of 7 parts, and 1200 of 2200 meters of film.

Still from A Nest of Noblemen, 1914.

Source: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дворянское_гнездо_%28фильм,_1914%29

The audit complains that even though Kinoresbel took four “programs” from Moscow, it only showed one film, Mask of Sin. We have not been able to find a movie by that name.13

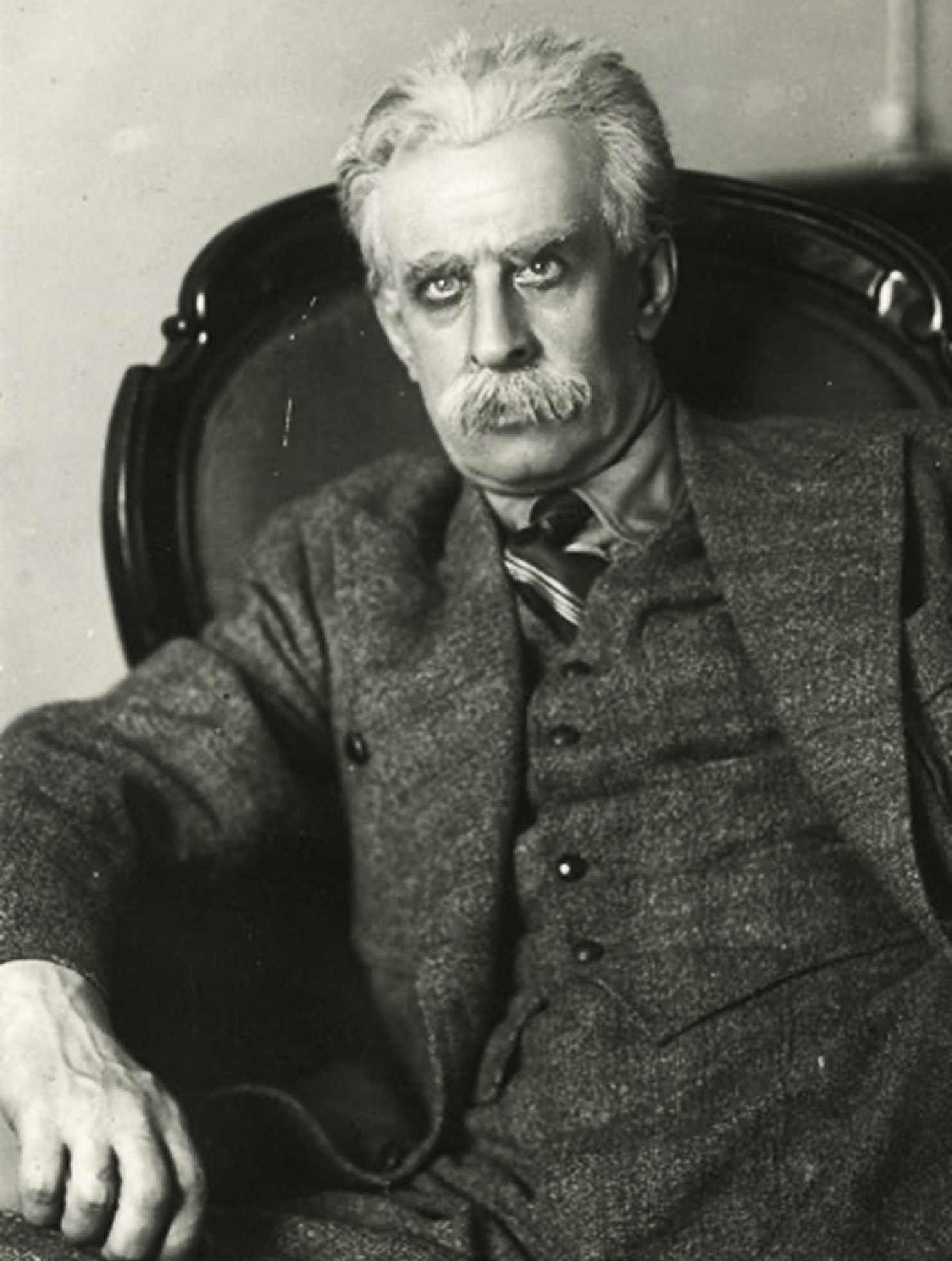

There is also mention of the film Three Portraits because it “remains unpaid.” This film was written and directed by Aleksandr Ivanovsky in 1919, adapted from a story by Ivan Turgenev. It featured Nikolai Rybnikov and Vera Dzheneeva.14

Nikolai Rybnikov.

Source: https://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/acter/m/sov/23808/bio/

Vera Dzheneeva.

Source: https://www.kino-teatr.ru/teatr/acter/w/empire/46106/bio/

The audit noted that Kinoresbel had not yet made the major repairs the cinemas needed but omitted that Kinoresbel had only been operating 45 days at the time the audit was conducted.

The audit also claimed that Kinoresbel’s predecessor, the Photo-Kino Department, “gave only profit to the state.” The audit also reported that after Kinoresbel deducted costs, “no profit will remain.”

There was more to come.

1 «Передача кинематографов кинотресту» [Transfer of cinemas to film trust]. Звезда (Zvezda) [Star], 07 Jun. 1922.

2 Balitsky, Deputy Head of the People’s Commissariat of Education, wanted to keep the cinemas in the City Department of Education. A later note makes it clear that the cinemas went to Kinoresbel. В Горисполком (“To the City Executive Committee”), 30 June 1922. Национальный архив Республики Беларусь (Natsional’nyi arkhiv Respubliki Belarus) [National Archives of Belarus (NARB)]. Fond 42, inv. 1, file 133, document 5.

3 Заведующему Белпожаротделом [Report to the Head of the Belarusian Fire Department]. NARB. Fond 42, inv. 1, file 1048, document 192.

4 Доклад [Report], 8 Mar. 1922. Государственный архив Минской области (Gosudarstvennyy arkhiv Minskoy oblasti) [State Archives of Minsk Region GAMn]. Fond 411, inv. 2, file 276, document 004; Доклад [Report] GAMn Fond 411, inv. 2, file 276, document 005-7.

5 Звезда (Zvezda) [Star], No. 122 (1145), Jun. 1922.

6 “В степи голода” [In the Steppe of Hunger]. Звезда. (Zvezda) [Star], No. 165 (1166), 14 Jul. 1922.

7 “Закупка заграничных кино-фильм” [Foreign Film Purchase]. Звезда (Zvezda) [Star], No. 165 (1166), 14 Jul. 1922. Belarus had its own Vneshtorg, the Belvneshtorg. The newspaper article is not definitive as to which organization Kinoresbel contacted.

8 “Ремонт кино-театров” [Cinema Theater Renovation]. Звезда. (Zvezda) [Star], No. 165 (1166), 14 Jul. 1922.

9 Rakhlin describes Sokolovsky as “a clerk for a certain Feigen in Gomel.” “В Народный Комиссариат Рабоче-Крестыянского Инспекции, Зам. Управляющего Киноресбел С. Рахлина, Объяснения Акту № 30” [To the People’s Commissariat of Workers’ and Peasants Inspection. From Deputy Manager of Kinoresbel S. Rakhlin. Explanation Regarding Act. No. 30], 1 Aug. 1922. NARB, Fond 42, inv. 1, file 133, document 39–42.

10 Probably one of the two Bystritsky brothers, Arnold and Mikhail, who had been in cinema from the beginning. Footnote: Гращенкова, И.Н. (Grashchenkova, I.N.). Кино Серебряного века: Русский кинематограф 10-х годов и Кинематограф Русского послеоктябрьского зарубежья 20-х годов (Kino Serebryanogo veka: Russkiy kinematograf 10-h godov i Kinematograf Russkogo posleoktyabr’skogo zarubezh’ya 20-h godov) [Cinema of the Silver Age: Russian Cinema of the 1910s and Cinema of the 1920s of the Russians Abroad Post October]. Министерство культуры Российской Федерации (Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation), 2005, p. 37,38, 107, 196, 215, 291; Вишневский, Вен (Vishnevsky, Ven). Документальные фильмы дореволюционной России, 1907–1916 (Dokumental’nye fil’my dorevolyutsionnoy Rossii, 1907–1916) [Documentaries of Pre Revolutionary Russia, 1907–1916]. Музей кино, Москва (Muzey kino, Moskva) (Museum of Cinema, Moscow), 1996, p. 34; Гинзбург, С. (Ginzburg, S.). Кинематография дореволюционной России (Kinematografiya dorevolyutsionnoy Rossii) [Cinematography of Pre Revolutionary Russia]. Искусство (Iskusstvo) (Art Publishing House), 1963, p. 144, 152, 165, 168, 230, 340.

11 There were two American versions in 1910 and a Russian version in 1915. We presume that the reference here is to the 1915 version but have no corroborating evidence.

12 “Dionysus’s Revenge” IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0005805/ Accessed 11 Nov. 2025.

13 “AKT” [Act], NARB, fond 42, inv. 1, file 133, document 35–36b.

14 “Три портрета (1919) — актёры и роли” [Three Portraits (1919) — Actors and Roles]. Kino-Teatr.ru, https://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/movie/sov/12984/titr/ Accessed Nov. 10, 2025.