Kinoresbel Gets Under Way

And the Knives Quickly Come Out

Kinoresbel was officially opened for business on June 1, 1922, its enemies quickly went after it, even as it went about routine work.

One of the first actions was to obtain jurisdiction of the cinemas which had been under the jurisdiction of the Glavpolitprosvet. It was reported in the June 1 edition of Zvezda that this had taken place.1

Less than a week later, the Red Army announced that it would be showing an old favorite at two cinemas it controlled, the Grotesque and the Spartak. The film, was A Tale of Dear Love of which Part II is the well known (to Russian film fans) as Silence, Sadness, Silence. (click here for more on when it was shown in Minsk). The print of the film, according to a Zvezda report, was brand new. And no special passes would be allowed. Everyone would have to pay for their tickets.2

Still of the cast members from the Silence, Sadness, Silence, 1918.

Source: http://www.everjazz.ru/playbill/item/3034/

On July 14, an article in Zvezda strongly criticized a play, In the Steppe of Hunger. While it was not a film, it was written by Samuel Rakhlin, the number two man in Kinoresbel.3 As the Communist Party organ, Zvezda was not printing a strong criticism of Rakhlin by accident. He should have been considered warned.

There were two other notable reports the same day. In one, it was reported that Kinoresbel had entered into an agreement with Vneshtorg (Ministerstvo vneshnei torgovli) the Ministry of Foreign Trade of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

The second Zvezda report said that the Giant cinema in Minsk, still called by that old name, and not its new one (Red Star), would be renovated at a cost of 5 million rubles.

Cinema Red Star, Minsk, 1920s.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/MinskPhotoHistoryNews

But someone behind the scenes clearly hated Kinoresbel. In July of 1922, just a month after Kinoresbel took the reins, the Narodny Komissariat Raboche-Krest'yanskoy Inspektsii of Belarus, in English the Workers and Peasants Inspection Committee, or Rabkrin, began an audit.

The audit purportedly covered January 1 to June 1, when the Photo-Cinema Department was running things, and then from June 1 to July 15.

The audit excoriated Kinoresbel for the choices of movies shown. The report made sure to mention the contracts with two men who had worked in the film business before the Bolshevik revolution: Mnushkin (to see more about the contract, click here), and Aronov (to see more on the Aronov contract click here). While the report does not specifically condemn the men, condemning the films Aronov provided and the way Mnushkin ran cinemas in Bobruisk and Gomel, was enough to send the message. The report also says that films were taken from the All Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Photo Committee (VUFKU) and from someone named Sokolovsky and a Muscovite named Vistritsky. The inference in all cases was that the material was, at best, unsuitable.

The audit says that the Minsk theaters Giant and Eden showed “artistic” films but never says what that means. The audit adds that the Modern theater, also in Minsk, showed films of a “sensational-detective character.”

The films, appear, for the most part to be old films from before the war and revolution. We have not been able to track down Suffering of Love (described in the report as a comedy), the Gambler, or Atonement of Blood. One of the films we were able to find was referred to in the report as A Nest of Nobles and known in English as A Nest of Noblemen (Дворянское гнездо). Yet another English title, per IMDB, is Dionysus's Anger.4 One of the biggest problem the auditors found with this film was that it was not complete. Kinoresbel had only 5 of 7 parts, and 1200 of 2200 meters of film.

Still from A Nest of Noblemen, 1914.

Source: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дворянское_гнездо_%28фильм,_1914%29

Kinoresbel definitely obtained one film from Moscow. The audit says that even though Kinoresbel took four “programs” from Moscow, it only showed one film, Mask of Sin. We have not been able to find any movies by that name.5

There is also mention of the film Three Portraits because it “remains unpaid.” It was written and directed by Aleksandr Ivanovsky in 1919, adapted from a story by Ivan Turgenev. It featured, among others, Nikolai Rybnikov and Vera Dzheneeva.6

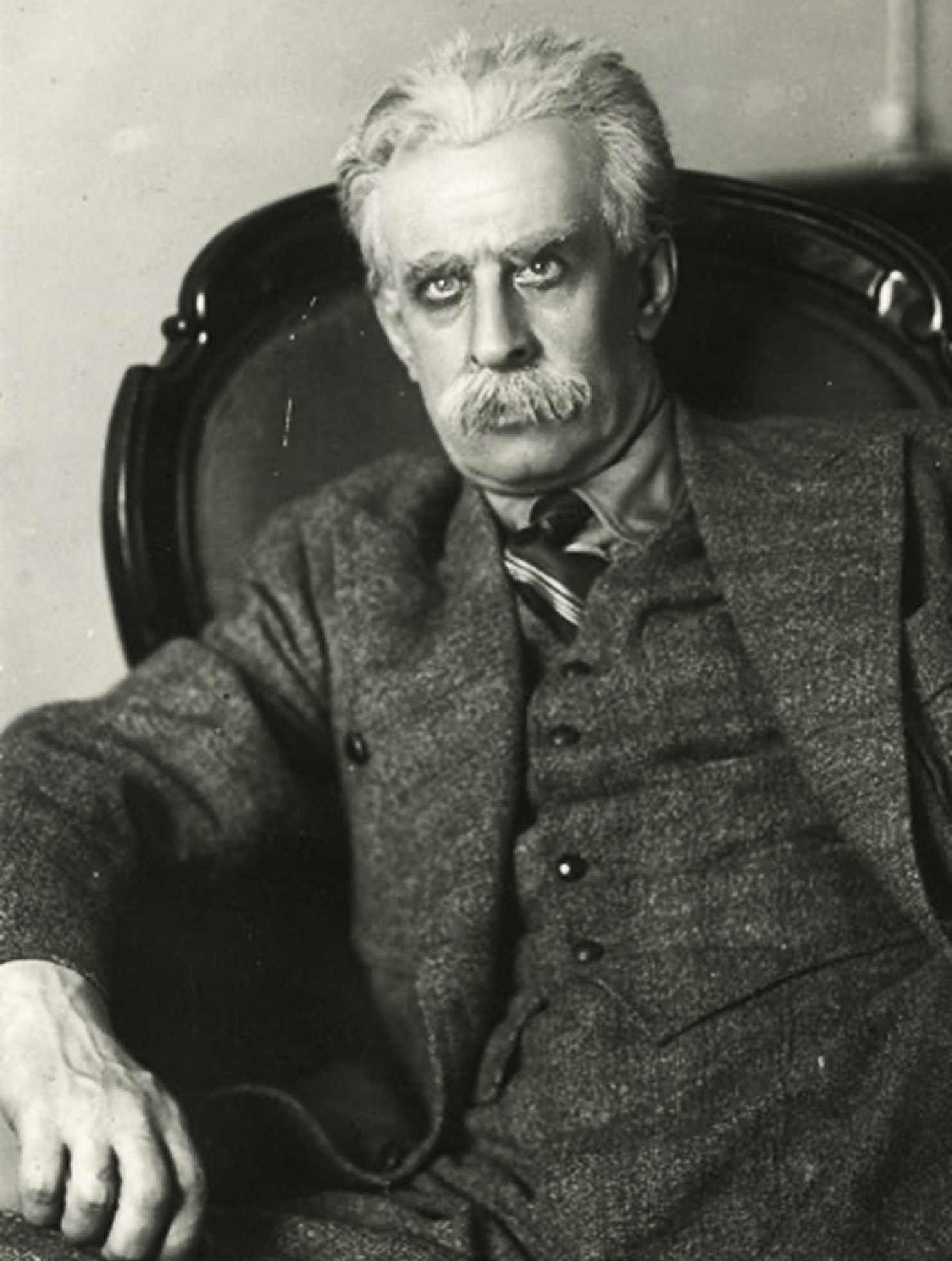

Nikolai Rybnikov.

Source: https://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/acter/m/sov/23808/bio/

Vera Dzheneeva.

Source: https://www.kino-teatr.ru/teatr/acter/w/empire/46106/bio/

The report noted that Kinoresbel had yet to undertake any of the major repairs its cinemas needed.

Regarding money making abilities, the audit noted that the Kinoresbel’s predecessor, the Photo-Cinema Department, “gave only profit to the state.” The auditor added that he estimated that after Kinoresbel deducted costs, “no profit will remain.”7

Kinoresbel did not take the report lying down.

1 “Передача кинематографов кинотресту” (“Transfer of cinemas to film trust”) (Звезда) (Zvezda) (Star) 07 Jun. 1922.

2 “Кинотеатры Гротеск и Спартак” (“Grotesque and Spartacus Cinemas”) (Звезда) (Zvezda) (Star) 11 Jun. 1922.

3 “В степи голода” (“In the Steppe of Hunger”) (Звезда) (Zvezda) (Star) 14 Jul. 1922.

4 “Dionysus’s Revenge” IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0005805/ Accessed 11 Nov. 2025.

5 “AKT”, Национальный архив Республики Беларусь (National Archives of Belarus, NARB), fond 42, opis 1, delo 133, document 35–36b.

6 Kino-Teatr.ru, “Три портрета (1919) — актёры и роли.” Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/movie/sov/12984/titr/

7 “AKT”, Национальный архив Республики Беларусь (National Archives of Belarus, NARB), fond 42, opis 1, delo 133, document 35–36b.